Article by Trevor Whittington, CEO WAFarmers, courtesy of Australian Rural & Regional News

06.10.2025

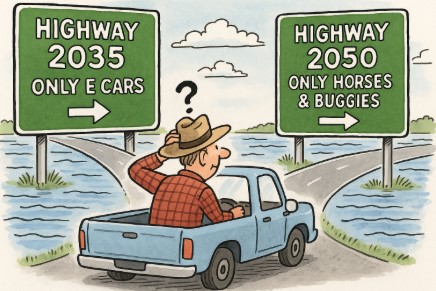

The ink is barely dry on Canberra’s new 2035 carbon targets, and the climate catastrophists are already eyeing 2050, the holy grail when net zero will finally be achieved.

Out in the Wheatbelt, most farmers shrug. Another distant date, another government promise, most have tuned out with the view that what I can’t see does not hurt me — a bit like the GRDC levy that nicks 1 per cent of farm-gate revenue.

But let’s be clear. Just like your compulsory research levy comes off your bottom line, the costs of the government’s carbon targets will also come off your bottom line. The difference is they will be buried deep in the supply chain of your costs of production, hidden under soothing titles like the Safeguard Mechanism. Notice how the government avoids words like tax or cost. Instead, it brands carbon measures with neutral or positive labels: the Capacity Investment Scheme, Powering the Regions Fund, Rewiring the Nation, the Emissions Reduction Fund, the National Reconstruction Fund, the Climate Solutions Package, the Nature Repair Market, the Climate Adaptation Strategy, the Net Zero Economy. These terms function as euphemisms. They signal policy direction while muting the reality: compliance costs, disguised taxes, or transfer payments. All sold as targeting “the big polluters.” But the fine print says otherwise.

The Safeguard Mechanism is the one to watch as it covers any facility emitting more than 100,000 tonnes of CO2-e a year. That net includes chemicals, fertilisers, fuel, grain handling, meat processing and shipping.

Under the government’s 2030 — and now 2035 — targets, each of the companies involved in the agricultural supply chain has a “baseline cap” set on their emissions of what is either plant food or pollution, depending on your perspective of CO2.

Under the old 2030 target, baselines were already stepping down by roughly 4.9 per cent a year — the easy steps. With the new 2035 target, the slope steepens. They must cut faster, year by year. There is no back-loading to the last minute in 2049. The cost burden accelerates now.

So when your fuel supplier exceeds its baseline, it must buy offsets. When your fertiliser producer runs out of engineering options to cut emissions, it must buy offsets. When your chemical supplier can’t find new technology to reduce emissions, it must buy offsets. When your trucking company has bought the latest Euro 6 trucks and still can’t cut emissions further, it too must buy offsets. None of the companies who are producing large amounts of carbon can magic away emissions overnight or reduce them at zero cost. They will do what corporates always do: pass the bill downstream. Straight to the producer. And that is where it stays, as few farmers have the ability to pass costs on to the consumer.

What’s the impact on a grain farmer’s cost of production under the 2035 target? No one in government will say, the National Farmers Federation has not done the work, neither has the Department of Agriculture. Why? Because I suspect no one wants to hear the answer.

We know that the federal government is in denial, Bowen tells us electricity prices will fall, but the Albanese government promised that three years ago before taking power — only for prices to rise sharply. Reading through the governments most recent announcement and you will find no modelling of costs, only promises of all the jobs that will be created by the billions of dollars that will need to be subsidised to fund the governments renewable targets.

Farmers know that building farm infrastructure comes at a cost to the bottom line. Any policy that costs hundreds of billions to build, wind and solar farms and transmission lines, must be paid for. Government targets will be paid for by the taxpayer, by business, or by consumer, and farmers are all three. ABARES modelling in 2023 found that decarbonisation policies could raise energy-intensive input prices by 10–30 per cent depending on carbon price trajectories, with fertiliser and diesel the most exposed. The Australian Farm Institute (AFI) warned a decade ago that an economy-wide carbon price could strip 8–13 per cent from farm output values once higher input costs and downstream processing were factored in. Those projections are no longer theoretical. They are built into Canberra’s 2035 targets.